Riprodurre e sottolineare tutto ciò che appartiene alla quotidianità attuale può essere osservato nel modo più pragmatico e realista, oppure lasciandosi andare alle emozioni che anche in un mondo ipertecnologico e avveniristico possono in qualche modo trovare il loro spazio per fuoriuscire e comunicare sensazioni completamente differenti da quelle che ci si aspetterebbe di ricevere. Alcuni creativi poi hanno la singolare caratteristica di mostrare anche il lato più visionario, in grado di trasformare le linee rigide e schematiche dei palazzi che vanno a costituire l’essenza stessa delle città in cui l’uomo moderno vive, in sinuosi e immaginari rifugi per la fantasia e affascinanti spunti per credere che in virtù di quel presente, ogni cosa nel futuro diventi possibile. La protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo gruppo di artisti visionari che hanno la capacità di mostrare il lato più bello, la parte più ammaliante di una modernità e di una vita urbana che laddove per taluni sembra essere una minaccia o una causa di isolamento dell’individuo, per altri invece è una realtà in cui calarsi e da cui prendere il meglio.

Nei primi anni del Novecento le città europee cominciavano a cambiare il loro aspetto, grazie alle innovative scoperte tecnologiche che avevano modificato lo stile di vita e le possibilità economiche della nuova borghesia e che, nel contempo, erano riuscite a infondere un’incrollabile fiducia verso il futuro che si stava costruendo e concretizzando giorno dopo giorno; nell’ambito di quel contesto in Italia nacque un movimento artistico che si proponeva di celebrare la fiducia e l’ammirazione per la velocità con cui tutto progrediva e si sviluppava facilitando così l’esistenza delle persone. La corrente artistica prese il nome di Futurismo e fu contraddistinta non solo dalla scomposizione delle immagini per enfatizzare il senso della velocità e del movimento che doveva catturare l’osservatore, ma anche da tonalità allegre e vivaci proprio per confermare quel senso di positività e di fiducia che aleggiava nell’aria e da cui gli artisti appartenenti al gruppo si facevano coinvolgere e travolgere. Quelli tra i futuristi che più subirono il fascino delle nuove città immortalandone diversi scorci furono Umberto Boccioni, le cui opere erano contraddistinte da tonalità vivide e da linee concave e convesse, come se tutto cuò che era rigido, come i muri dei palazzi, potesse a sua volta adeguarsi e plasmarsi all’entusiasmo verso la vita e verso il domani, e Fortunato Depero, talmente affascinato dalle moderne architetture da tentare la fortuna nella metropoli più futurista del mondo, New York, e che lasciò ammaliare dai meravigliosi palazzi fatti di acciaio e vetrate al punto di dedicargli molte opere. Qualche anno più tardi proprio negli Stati Uniti, vide la luce un movimento che da un lato riprendeva la centralità dei soggetti urbani e le nuove costruzioni industriali che avevano contraddistinto alcuni esponenti del Futurismo, e dall’altro si ispirava al coevo Cubismo per la schematizzazione geometrica degli edifici; il Precisionismo, questo il nome della corrente statunistense, mostrò l’altro volto del futuro, quello più orientato all’industrializzazione del paesaggio americano dove l’essere umano è un dettaglio trascurabile, un’opzione che non viene considerata come rilevante nell’ambito dell’osservazione del progresso, a sua volta non più travolgente ed entusiasmante come nel Futurismo bensì forse più equilibrato e realista nello sguardo verso ciò che apparteneva alla quotidianità. L’artista cinese Cui Jie sembra mescolare la vivacità e la positività del Futurismo al tratto realista e schematico del Precisionismo, anche se in lei la geometricità si perde dentro la decontestualizzazione che infonde alle sue tele, come se gli edifici che ama raccontare fossero in qualche modo sospesi nel tempo, appartenenti a una dimensione che si sfuma nel sogno, nell’immaginario tendente a rendere ogni cosa più piacevole.

L’ammirazione dell’artista nei confronti di tutto ciò che è urbano emerge dalla piacevolezza delle tonalità tenui con cui descrive pensiline, grattacieli, hotel, palazzi di cui mette in risalto alcuni dettagli, filtrati da una lente di ingrandimento attraverso cui genera l’effetto ottico del lasciar fuoriuscire dall’immagine generale un particolare, puntandovi l’attenzione e di conseguenza trasformando l’aspetto reale in qualcosa di più onirico.

Il Futurismo si manifesta dunque nelle linee che infondono alle opere il senso di movimento, non più rapido come nella corrente originaria del Novecento bensì fluttuante, come se tutto fosse in costante e lenta modificazione, come se l’avvenirismo in cui sono immerse le sue rappresentazioni urbane fosse in procinto di diventare presente un attimo dopo; d’altro canto però non si può non notare la definitezza del tratto pittorico, la presenza di un rigore grafico, vicino al Precisionismo. attraverso il quale Cui Jie riesce a trasmettere un senso di perfezione cristallina, iperdefinita come solo la tecnologia moderna è in grado di produrre, avvolgendo però tutta l’atmosfera di una gamma cromatica tenue, morbida, come se nel suo mondo la contemporaneità non potesse staccarsi dall’immaginario, dalla magia del sogno, dalla sofficità con cui anche l’apparenza più schematica può essere osservata.

La fascinazione subita dall’artista davanti alle città più moderne al mondo si traduce così in universo ideale dove ciò che viene messo in evidenza è lo scintillio di quelle innovazioni che hanno permesso all’essere umano di dare vita a edifici in grado di strabiliare lo sguardo e indurre l’osservatore a sentirsi parte di quella maestosità da un lato distaccata e quasi intimorente ma dall’altro, grazie al filtro del coinvolgimento emotivo, assolutamente accogliente.

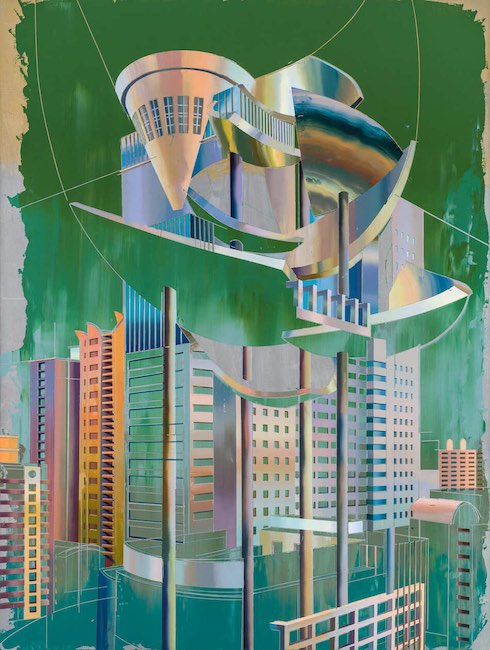

Nella tela New Taipei City Hall infatti, Cui Jie racconta l’imponenza dell’edificio rigoroso e geometrico, ma poi nella parte superiore ne mette in risalto, ingrandendoli, alcuni dettagli, quasi per ammorbidire l’aspetto generale, per invitare l’osservatore a immergersi nella magia che ogni cosa, anche quella apparentemente più austera, può nascondere in sé svelandosi solo a chi ha la sensibilità di andare oltre l’armatura esterna; i colori sono in predominanza verdi accostati a tonalità pastello con cui vengono alleggerite le linee grafiche del palazzo che nella parte inferiore, anziché mostrare la solida base, sembra divenire evanescente, infondendo nello sguardo la sensazione che stia galleggiando nell’etere. In qualche modo la Jie sembra suggerire la necessità di non rimanere troppo a lungo legati a radici che spesso trattengono dalla spinta verso le infinite possibilità costituite dal futuro e dal moto perpetuo, anche se a volte impercettibile, che ogni certezza porta con sé.

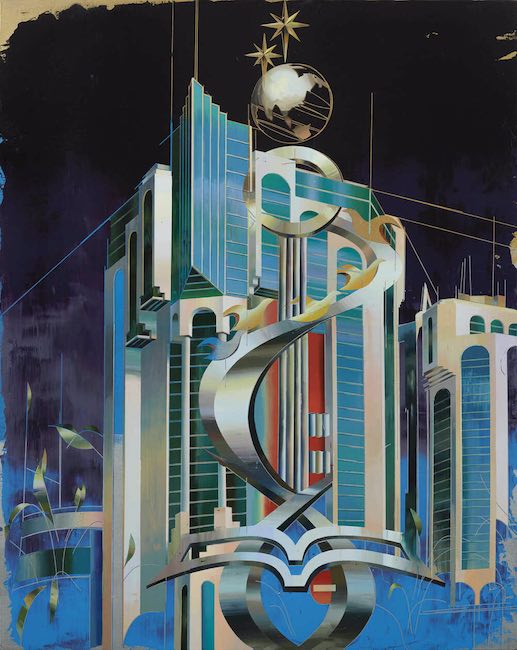

In Shangai Federation of Industry Commerce Building il senso del costante progresso e sviluppo è accentuato dalla quasi totale inconsistenza dell’edificio, in questa tela più che in altre è sottolineata la sospensione del palazzo perché è proprio al suo interno che si concretizzano le modificazioni maggiori, le scelte economiche e industriali che trasformano la vita degli individui; Cui Jie abbraccia queste opzioni con positività, senza il timore dei cambiamenti appartenenti invece alla maggior parte delle persone, piuttosto ne mette in risalto la positivita convinzione che tutto tenda verso un miglioramento, verso maggior benessere e attenzione verso l’evoluzione dell’umanità. Gli elementi metallici incrementano la sensazione di transizione tra passato e presente che tende verso il luminoso futuro contraddistinto dal rosa.

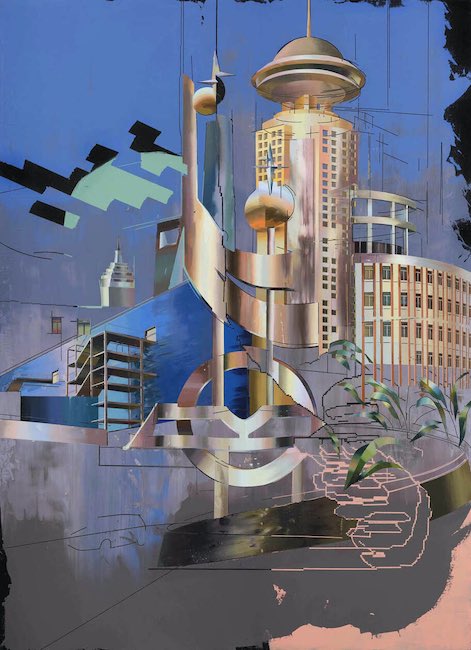

Nella tela Basildon l’artista narra uno scorcio della cittadina inglese situata nell’Essex meridionale, contraddistinta da edifici bassi, da un grande orientamento industriale e da strutture in armonia con la campagna circostante; Cui Jie ne riproduce uno scorcio che non è sufficiente a distinguerla da qualsiasi altra città ma di fatto è esattamente ciò che ha colpito l’artista nel momento in cui l’ha visitata, sottolineandone l’aspetto rigoroso e al contempo leggero grazie alla presenza di vetrate che sembrano fondersi con l’ambiente. In questo caso la pensilina assume un aspetto quasi Art Déco, nella sua accezione più avveniristica riscontrabile negli edifici statunitensi degli anni Venti del Novecento, e tutto ciò che cattura l’artista è l’armonia tra linee curve e sinuose e la schematicità del resto della costruzione, come se l’immagine fosse una metafora di tutto ciò di cui l’essere umano necessita per rimanere in piedi e tirare fuori il meglio da se stesso, accettando cioè di trovare un equilibrio tra emozione e razionalità.

Cui Jie ha al suo attivo mostre personali a Manchester, Londra, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Dublino e Jaffa, e collettive a Taipei, Hong Kong, Guangdong, New York, Pechino, Shanghai, Tampa, Florida, San Pietroburgo, Oklahoma City, Hangzhou.

CUI JIE-CONTATTI

Sito web: www.pilarcorrias.com/artists/44-cui-jie/

Instagram: www.instagram.com/cuijie83/

The visionary view of modernity in Cui Jie’s Neofuturism, when cities are dressed in the charm of dreams

Reproducing and emphasising everything that belongs to current everyday life can be observed in the most pragmatic and realistic way, or by letting go of the emotions that even in a hyper-technological and futuristic world can somehow find their way out and communicate feelings that are completely different from what one would expect. Some creatives then have the singular characteristic of showing even the most visionary side, capable of transforming the rigid and schematic lines of the buildings that make up the very essence of the cities in which modern man lives, into sinuous and imaginary refuges for the imagination and fascinating cues to believe that by virtue of that present, everything in the future becomes possible. Today’s protagonist belongs to this group of visionary artists who have the ability to show the most beautiful side, the most bewitching part of a modernity and urban life that whereas for some it seems to be a threat or a cause of isolation of the individual, for others it is a reality in which to immerse oneself and from which to take the best.

In the early years of the 20th century European cities were beginning to change their appearance, thanks to the innovative technological discoveries that had changed the lifestyle and economic possibilities of the new bourgeoisie and that, at the same time, had succeeded in instilling an unshakeable confidence in the future that was being built and realised day by day; within that context was born an artistic movement in Italy that aimed to celebrate the confidence and admiration for the speed with which everything was progressing and developing, thus facilitating people’s existence. The artistic current took the name Futurism and was characterised not only by the decomposition of images to emphasise the sense of speed and movement that was meant to capture the observer, but also by cheerful and lively tones precisely to confirm that sense of positivity and confidence that hung in the air and by which the artists belonging to the group became involved and overwhelmed. The Futurists who were most fascinated by the new cities and immortalised various views of them were Umberto Boccioni, whose artworks were characterised by vivid tones and concave and convex lines, as if everything that was rigid, such as the walls of buildings, could in turn adapt and shape itself to the enthusiasm for life and tomorrow, and Fortunato Depero, who was so fascinated by modern architecture that he tried his luck in the world’s most futurist metropolis, New York, and was so enchanted by the marvellous buildings made of steel and glass that he dedicated many canvases to them.

A few years later, precisely in the United States emerged a movement that on the one hand took up the centrality of urban subjects and the new industrial constructions that had distinguished some exponents of Futurism, and on the other was inspired by contemporary Cubism for the geometric schematisation of buildings; Precisionism, this was the name of the US current, showed the other face of the future, the one more oriented towards the industrialisation of the American landscape where the human being was a negligible detail, an option that was not considered as relevant in the observation of progress, in turn no longer overwhelming and exciting as in Futurism but perhaps more balanced and realistic in its gaze towards what belonged to the everyday. The Chinese artist Cui Jie seems to mix the liveliness and positivity of Futurism with the realist and schematic trait of Precisionism, even if, in her paintings, geometricity is lost in the decontextualisation that she infuses her canvases with, as if the buildings she likes to depict were somehow suspended in time, belonging to a dimension that fades into the dream, into the imaginary that tends to make everything more pleasant. The artist’s admiration for all that is urban emerges from the pleasantness of the soft tones with which she describes canopies, skyscrapers, hotels, buildings of which she highlights certain details, filtered through a magnifying glass through which she generates the optical effect of letting a detail escape from the general image, focusing attention on it and consequently transforming the real aspect into something more dreamlike. Futurism is thus manifested in the lines that imbue the artworks with a sense of movement, no longer rapid as in the original 20th century current, but fluctuating, as if everything were in a constant, slow modification, as if the futurism in which her urban representations are immersed was about to become present a moment later; on the other hand, however, one cannot fail to notice the definiteness of the pictorial stroke, the presence of a graphic rigour, close to Precisionism, through which Cui Jie manages to convey a sense of crystalline perfection, hyper-defined as only modern technology is capable of producing, while enveloping the entire atmosphere in a soft, mellow chromatic range, as if in her world contemporaneity could not detach itself from the imaginary, from the magic of dreams, from the softness with which even the most schematic appearance can be observed.

The artist’s fascination with the world’s most modern cities is thus translated into an ideal universe where what is highlighted is the sparkle of those innovations that have allowed human beings to give life to buildings capable of astounding the gaze and inducing the observer to feel part of that majesty that is on the one hand detached and almost intimidating but on the other, thanks to the filter of emotional involvement, absolutely welcoming. In the canvas New Taipei City Hall, Cui Jie recounts the grandeur of the rigorous and geometric building, but then, in the upper part, she emphasises and enlarges some of its details, almost as if to soften the general aspect, to invite the observer to immerse himself in the magic that everything, even the most apparently austere thing, can hide within itself, revealing itself only to those who have the sensitivity to go beyond the external armour; the colours are predominantly green combined with pastel shades that lighten the graphic lines of the palace, which in the lower part, instead of showing the solid base, seems to become evanescent, instilling in the eye the feeling that it is floating in the ether. In a way, Jie seems to suggest the need not to remain tied to roots for too long, often holding back from the drive towards the infinite possibilities constituted by the future and the perpetual, albeit sometimes imperceptible, motion that every certainty brings with it. In Shanghai Federation of Industry Commerce Building, the sense of constant progress and development is accentuated by the almost total insubstantiality of the building. In this canvas more than in others is emphasised the suspension of the palace because it is within it that the greatest changes take place, the economic and industrial choices that transform the lives of individuals; Cui Jie embraces these options with positivity, without the fear of change that most people have, rather she underlines the positive belief that everything tends towards improvement, towards greater well-being and attention to the evolution of humanity. The metallic elements increase the feeling of transition between past and present tending towards the bright future marked by pink. In the painting Basildon, the artist depicts a glimpse of the small English town in southern Essex, characterised by low buildings, a great industrial orientation and structures in harmony with the surrounding countryside; Cui Jie reproduces a view of it that is not enough to distinguish it from any other city but in fact is exactly what struck the artist when she visited it, emphasising its rigorous yet light appearance thanks to the presence of glass windows that seem to merge with the environment. In this case, the canopy takes on an almost Art Deco appearance, in its most futuristic sense found in the american buildings of the 1920s, and all that captures the artist is the harmony between the curved, sinuous lines and the schematic nature of the rest of the construction, as if the image were a metaphor for all that human beings need to stay on their feet and bring out the best in themselves, that is, to find a balance between emotion and rationality. Cui Jie has to her credit solo exhibitions in Manchester, London, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Dublin and Jaffa, and group exhibitions in Taipei, Hong Kong, Guangdong, New York, Beijing, Shanghai, Tampa, Florida, St. Petersburg, Oklahoma City, Hangzhou.