La percezione di tutto ciò che viene vissuto nella contemporaneità è molto spesso legata a tutte quelle osservazioni introspettive, alle inquietudini e alle insicurezze che fanno parte in modo quasi imprescindibile della vita moderna e che inducono gli artisti ad approfondirne i risvolti, a evidenziarne le sfumature più interiori lasciando emergere i disagi, le difficoltà e le incertezze dell’essere umano così come l’incapacità di confrontarsi in maniera consapevole con esse. Tuttavia esistono anche alcuni artisti che hanno un approccio diverso alla realtà osservata, ed è attraverso la loro spiccata sensibilità che riescono a farne emergere la delicatezza, la magia che avvolge ogni frangente quotidiano senza che riesca a essere colto se non attraverso la loro capacità di andare oltre e di porsi in posizione di apertura verso la bellezza e la piacevolezza che si nasconde nelle pieghe della quotidianità. La protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo gruppo di creativi.

Il movimento del Realismo ha dominato il Diciannovesimo secolo, restando molto a lungo un privilegio esclusivo dei nobili e dei nuovi borghesi che cominciarono ad avere potere economico in virtù dell’industrializzazione poiché in qualche modo la corrente artistica era legata inizialmente ai ritratti su commissione, in cui venivano immortalati i volti e gli interni delle abitazioni dei committenti e delle loro famiglie. Con il passare dei decenni però i grandi rappresentanti di questo stile cominciarono a raccontare i cambiamenti epocali e sociali che si stavano susseguendo mettendo in evidenza le lotte di classe, come nel celeberrimo Il Quarto stato di Pellizza da Volpedo, o immortalando i momenti di lavoro degli artigiani e dei contadini, come nelle incredibili opere di Gustave Courbet, proprio per lasciare traccia di una realtà che non poteva più essere ignorata o trascurata. Avvicinandosi al Novecento tuttavia, quando l’Espressionismo fece sentire in modo forte la sua innovativa voce nei confronti dell’approccio pittorico, del suo sconvolgere l’osservatore in virtù delle emozioni gridate attraverso lo stravolgimento di tutte le regole accademiche, il Realismo sembrò essere superato, non al passo con i nuovi tempi che si stavano delineando perché l’avvento delle nuove tecnologie di riproduzione delle immagini e la conseguente evoluzione della fotografia, davano la possibilità alle persone di avere immagini vere a un costo decisamente meno elevato. Ma intorno agli anni Venti del Ventesimo secolo cominciò ad avvertirsi l’esigenza di tornare a un nuovo ordine, di ricominciare a recuperare alcune regole classiche permeandole però di nuovi significati e generando così una profonda trasformazione del Realismo che da un lato esplorò quel mistero sottile che avvolge la realtà e l’essere umano infondendo nei personaggi un senso di straniamento prendendo il nome di Realismo Magico, dall’altro invece si propose di esplorare l’individuo, e ciò che lo circonda, da un punto di vista più psicologico, indagando sul vivere della nuova classe media che pur avendo tutto doveva fare i conti con una profonda solitudine. Edward Hopper, massimo esponente del Realismo Americano, lasciò intense testimonianze di questo approccio. L’artista di origini venete ma da anni residente a Bolzano Stefania Miceli arricchisce le sue opere di forte impronta realista di un’atmosfera avvolgente, quasi metafisica, come se in qualche modo la sua capacità di ascolto di tutto ciò che ruota intorno ai protagonisti dei suoi dipinti la ponesse in contatto con tutte quelle energie sottili che ammorbidiscono l’ambiente circostante e che infondono un’essenza poetica alle azioni, agli sguardi, alle pose che diventano la parte più rilevante della tela.

Si respira quasi un’atmosfera retrò, nostalgica nei confronti di un tempo in cui le emozioni e le sensazioni erano più semplici, più pure, e non si può non andare con la memoria emotiva verso le immagini romantiche del cinema muto, quello del grande Charlie Chaplin, del quale la Miceli riprende la morbida suggestione con cui avvolge non solo i personaggi bensì anche gli oggetti.

La sua tendenza a dar vita a sfondi impalpabili, soffici all’apparenza, si associa alla sua caratteristica di scegliere per le sue opere tonalità polverose, terrose, quasi sempre in scala di grigi arricchite dagli ocra, dai marroni, dai sabbia, infondendo pertanto a tutti i suoi dipinti un’aria fuori dal tempo, un’ambientazione sospesa che da un lato sembra appartenere al passato infondendo così una sensazione malinconica, ma dall’altro invece si propaga nel presente come se nel magico mondo dell’arte, così come in quello dell’immaginazione e del sentire di Stefania Miceli, quell’unione fosse possibile.

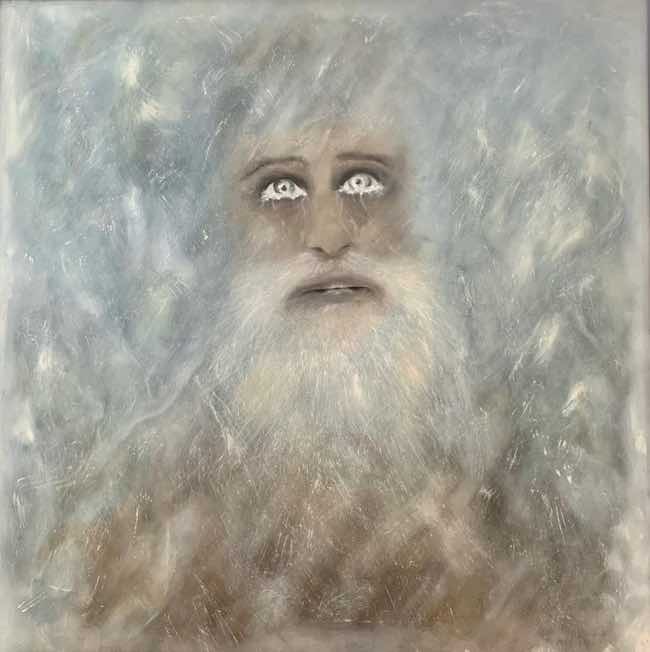

L’immaterialità degli sfondi viene realizzata attraverso una mescolanza di oli, acrilici e gesso sulla tela che si trasforma dunque in un universo a cui dare voce, un racconto di emozioni, di percezioni, di sottile palpitare in virtù del quale l’immagine riprodotta si amalgama con le energie che sembrano fuoriuscire dagli sfondi luminosi e al tempo stesso soffusi che contribuiscono a propagarle.

L’opera La lattaia racconta di un’abitudine antica e ormai superata, quella delle famiglie del dopoguerra di ricevere il latte direttamente a casa, in grossi bidoni da suddividere poi per tutti i componenti, e dunque la donna che si occupa della vendita di quello che era considerato un bene necessario è immortalata da Stefania Miceli su una bicicletta che induce l’osservatore a immaginarla caricare uno dei bidoni per portarlo a destinazione; non è difficile percepire in questa tela, come nelle altre, l’importanza che per l’artista ricopre il ruolo della donna, protagonista anche in un periodo in cui la maggior parte dei ruoli professionali era svolta da uomini. La Miceli narra invece una realtà diversa, quella di chi ha avuto il coraggio di tirare fuori la propria determinazione e conquistarsi un posto nella società diverso da quello che in quei tempi le voleva essere attribuito, quello di madre e moglie senza poter avere un’indipendenza solo sua.

Anche nel dipinto Il golf emerge di nuovo l’approccio sognante nei confronti, in questo caso, di uno sport che evidentemente è una parte importante della vita della protagonista, anche lei determinata a entrare in un ambiente che nell’immaginario comune è costituito prevalentemente da uomini; ma la donna ritratta non si cura della generalizzazione, lei sceglie di immergersi nella natura e confrontarsi con se stessa respirando l’energia che dalla sua passione fuoriesce, concentrandosi per raggiungere il suo obiettivo, quello di centrare la buca. L’opera può essere interpretata come metafora del conseguire un risultato a cui troppo spesso le donne rinunciano per dare la priorità alla famiglia, quasi come se fosse un loro dovere mettersi da parte. Per Stefania Miceli invece non è così, la donna è attrice principale del suo destino come della sua vita, e descrive personaggi femminili sicuri di sé, determinati, che però sono perfettamente in grado di mantenere la loro dolcezza e la loro femminilità.

Altrettanto sensibile è l’approccio verso l’uomo di cui l’artista riesce a far fuoriuscire il lato morbido, poetico e alchemico come nell’opera Musicista di strada in cui il legame con la musica, con le note del trombone che sembrano avvolgere non solo il protagonista bensì anche l’osservatore in virtù della capacità di Stefania Miceli di lasciar palpitare la figura al centro della scena ma anche il luogo non luogo dentro cui la colloca, come se l’unica cosa che contasse è il trasporto provato nel momento in cui il suono esce dal suo strumento. La sensazione è accresciuta dalla scelta di sfumare completamene il contorno destro dell’uomo che dunque diviene impalpabile quanto invece la musica assume concretezza e rilevanza in virtù della capacità di sospendere la realtà per il tempo della melodia. Anche in quest’opera le tonalità sono polverose, cipriate, infondendo nell’osservatore la medesima emozione nostalgica delle fotografie color seppia, appartenenti romanticamente a un passato non troppo vicino da essere ancora nitido, ma non troppo lontano da essere dimenticato.

Stefania Miceli inizia fin dalla giovane età a misurarsi con una creatività intensa in cui manifesta un’inconsapevole tendenza introspettiva, lei che invece nella quotidianità è travolgente e dinamica; ha al suo attivo numerose mostre collettive ed è socia dell’associazione Club Arcimboldo di Bolzano e dell’associazione internazionale Il Carro delle Muse.

STEFANIA MICELI-CONTATTI

Email: stefaniamiceli1@gmail.com

stefaniamiceliarte@yahoo.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/stefania.miceli.3363

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100085692351635

Stefania Miceli, the journey through the subtle alchemy that envelops reality

The perception of all that is experienced in the contemporary world is very often linked to all those introspective observations, anxieties and insecurities that are an almost inescapable part of modern life and that lead artists to delve into its implications, to highlight its most interior nuances, allowing to emerge the discomforts, difficulties and uncertainties of the human being, as well as the inability to consciously confront them. However, there are also some artists who have a different approach to the reality they observe, and it is through their marked sensitivity that they succeed in bringing out the delicacy, the magic that envelops every daily occurrence without it being grasped except through their ability to go beyond it and to place themselves in a position of openness towards the beauty and pleasantness that is hidden in the folds of everyday life. Today’s protagonist belongs to this group of creatives.

The Realism movement dominated the 19th century, remaining for a long time an exclusive privilege of the nobility and the new bourgeoisie who began to have economic power by virtue of industrialisation, as in some ways the artistic current was initially linked to commissioned portraits, in which the faces and interiors of the homes of patrons and their families were immortalised. As the decades went by, however, the great representatives of this style began to recount the epochal and social changes that were taking place, highlighting class struggles, as in Pellizza da Volpedo’s famous Il Quarto stato, or immortalising the work of artisans and peasants, as in Gustave Courbet’s incredible artworks, precisely in order to leave a trace of a reality that could no longer be ignored or neglected. Approaching the 20th century, however, when Expressionism made its innovative voice heard loudly against the pictorial approach, of its shocking the observer by virtue of the emotions shouted through the disruption of all academic rules, Realism seemed to be outdated, not in step with the new times that were emerging because the advent of new image reproduction technologies and the consequent evolution of photography, gave people the possibility of having real images at a much lower cost. However, around the 1920s, began to be felt the need to return to a new order, to recover certain classical rules, permeating them with new meanings and thus generating a profound transformation of Realism, which on the one hand explored the subtle mystery that envelops reality and the human being, infusing characters with a sense of estrangement and taking on the name of Magic Realism, on the other hand set out to explore the individual, and his surroundings, from a more psychological point of view, investigating the lives of the new middle class who, despite having everything, had to come to terms with a profound loneliness. Edward Hopper, the greatest exponent of American Realism, left intense evidence of this approach. The artist, originally from Veneto but for many years resident in Bolzano, Stefania Miceli enriches her artworks with a strong realist imprint with an enveloping, almost metaphysical atmosphere, as if somehow her ability to listen to everything that revolves around the protagonists of her paintings put her in contact with all those subtle energies that soften the surrounding environment and infuse a poetic essence to the actions, the glances, the poses that become the most relevant part of the canvas.

One breathes almost a retro atmosphere, nostalgic for a time when emotions and sensations were simpler, purer, and one cannot help but go with one’s emotional memory to the romantic images of silent cinema, that of the great Charlie Chaplin, whose soft suggestion Miceli uses to envelop not only the characters but also the objects. Her tendency to give life to impalpable backgrounds, soft in appearance, is associated with her characteristic of choosing dusty, earthy tones for her artworks, almost always in greyscale enriched by ochres, browns and sand, thus infusing all her paintings with an air of timelessness, a suspended ambience that on the one hand seems to belong to the past, thus instilling a melancholic feeling, but on the other hand spreads into the present as if in the magical world of art, as well as in that of Stefania Miceli’s imagination and feeling, that union were possible. The immateriality of the backgrounds is realised through a mixture of oils, acrylics and chalk on the canvas, which is thus transformed into a universe to be given voice, a tale of emotions, perceptions, of subtle palpitations by virtue of which the reproduced image amalgamates with the energies that seem to emanate from the luminous yet suffused backgrounds that help to propagate them. The painting The Milkmaid recounts an ancient and now outdated custom, that of post-war families to receive milk directly at home, in large bins to be then divided up for all the members, and thus the woman who is responsible for the sale of what was considered a necessary good is immortalised by Stefania Miceli on a bicycle that induces the observer to imagine her loading one of the bins to take it to its destination; it is not difficult to perceive in this canvas, as in the others, the importance for the artist of the role of women, protagonists even at a time when most professional roles were carried out by men. Instead, Miceli narrates a different reality, that of someone who had the courage to pull out her determination and conquer a place for herself in society that was different from the one it was given at the time, that of mother and wife without being able to have an independence of her own.

In the painting Golf, emerges once again the dreamy approach, in this case for a sport that is clearly an important part of the life of the protagonist, who is also determined to enter an environment that in the common imagination is predominantly made up of men; but the woman portrayed does not care about generalisation, she chooses to immerse herself in nature and confront herself by breathing in the energy that emanates from her passion, concentrating on achieving her goal, that of hitting the hole. The artwork can be interpreted as a metaphor for achieving something that women too often give up in order to prioritise their families, almost as if it were their duty to step aside. For Stefania Miceli, however, this is not the case; the woman is the main actress of her destiny as well as of her life, and she describes self-confident, determined female characters who are nevertheless perfectly able to retain their sweetness and femininity. Equally sensitive is the approach to the man whose soft, poetic and alchemic side the artist succeeds in bringing out, as in the painting Street Musician in which the link with music, with the notes of the trombone that seem to envelop not only the protagonist but also the observer by virtue of Stefania Miceli’s ability to let the figure at the centre of the scene but also the non-place in which she places it palpitate, as if the only thing that counts is the transport felt at the moment the sound comes out of her instrument. The sensation is heightened by the choice of completely blurring the right contour of the man, who thus becomes as impalpable as the music takes on concreteness and relevance by virtue of its ability to suspend reality for the time of the melody. In this artwork too, the tones are dusty, powdery, instilling in the observer the same nostalgic emotion as in sepia-toned photographs, romantically belonging to a past not too near to be still sharp, but not too far away to be forgotten. Stefania Miceli began at a young age to measure herself with an intense creativity in which she manifests an unconscious introspective tendency, she who instead in everyday life is overwhelming and dynamic; she has numerous collective exhibitions to her credit and is a member of the Club Arcimboldo association in Bolzano and the international association Il Carro delle Muse.