Molto spesso l’arte contemporanea tende a dimenticare le origini da cui proviene, quel passato che ha segnato inevitabilmente il percorso successivo e che di fatto si concretizza oggi con un atteggiamento più libero nella scelta dello stile espressivo che ciascun creativo desidera utilizzare. Vi sono però alcuni artisti che, pur mostrando un approccio non convenzionale alla tela, sentono il bisogno di raccontare di quel passato, come se le loro opere dovessero diventare un modo per indurre il fruitore a non perdere la memoria su quanto importanti siano stati i maestri che hanno scritto, con il loro talento, la storia dell’arte più o meno recente. Il protagonista di oggi, attraverso uno stile ironico e irriverente, costituisce una voce solista nel panorama artistico internazionale, mescolando sapientemente due tra i principali stili del secolo scorso e arricchendoli di un tocco nostalgico che però viene reso divertente e fuori dagli schemi dalla sua capacità di giocare con il tempo e con lo spazio.

Il tema della decontestualizzazione cominciò a emergere verso gli anni Venti del Novecento, quando cioè un gruppo di artisti francesi delineò le basi teoriche di un movimento, il Surrealismo, considerato l’evoluzione del Dadaismo, che voleva focalizzare la sua attenzione sul mondo della psiche e dell’inconscio; dalle idee di André Breton scaturirono una serie di interpretazioni personali, sulla base dell’approccio pittorico di ciascun aderente alla corrente artistica, tutte però con un denominatore comune, quello di ingannare lo sguardo dell’osservatore con un’apparenza estetica vicina alla realtà ma di fatto conducendolo in un mondo onirico fatto di incubi, di inquietudini, di contesti improbabili eppure potenzialmente possibili all’interno della dimensione del sogno. Laddove l’inquietudine prevaleva e si concretizzava con scenari post-apocalittici nelle opere di Salvador Dalì e di Max Ernst, nei surrealisti belgi come René Magritte e Paul Delvaux la sensazione suscitata era di riflessione, di indagine su quelle energie sottili portate alla luce dall’artista e comunicate al fruitore che in quelle dimensioni non poteva che perdersi rimanendone affascinato per il significato profondo nascosto dentro l’immagine. La decontestualizzazione, sebbene emersa in maniera differente e con scopi divergenti e distanti da quella del Surrealismo, fu ripresa da quello che viene considerato il genio ideatore e fondatore della Pop Art, quell’Andy Warhol che fu in grado di intuire l’importanza di rivolgersi a un pubblico più ampio, alla nuova borghesia emergente che pur non avendo avuto una formazione culturale legata all’arte, poteva comunque apprezzare e desiderare di portarne la bellezza nelle proprie case. Dunque rendere protagonisti i nuovi miti, i simboli di una quotidianità e di una corsa al consumismo che stava contraddistinguendo l’America degli anni Cinquanta del Novecento condusse la Pop Art, declinata e adattata all’intento creativo dei vari artisti che vi aderirono, verso una popolarità planetaria. In ogni caso quei simboli, quei nuovi miti, i personaggi dei fumetti, gli attori di Hollywood, le bandiere, erano non solo estrapolati dal contesto originario, ma messi in evidenza attraverso sfondi a colori forti, la loro apparenza cromatica veniva modificata e adeguata all’estro dell’autore dell’opera.

L’artista italiano Angelo Accardi, originario di un piccolo paese del sud Italia ma formatosi presso l’Accademia d’Arte di Napoli, ha sviluppato nel tempo uno stile pittorico decisamente originale ed eccentrico, frutto di una fusione di differenti correnti artistiche del Novecento che però vengono riattualizzate e assecondate al suo impulso creativo; pertanto la decontestualizzazione del Surrealismo, che si manifesta con la presenza dei suoi immancabili struzzi all’interno di ambienti domestici o nelle strade delle città e con un’apparenza decisamente umana dal punto di vista delle espressioni del muso, si unisce a simboli dei fumetti o dei film moderni come i Minions, i Simpson, Mister Bean, l’immancabile Mickey Mouse rendendo dunque irrimediabilmente Pop la sua produzione artistica.

Ma Angelo Accardi non si ferma qui perché oltre a descrivere gli ambienti in cui colloca i suoi personaggi con tocco realista trasformato però da una gamma cromatica espressionista, ciò che rende persino più uniche le sue tele sono quei continui riferimenti alle opere d’arte del passato, quel mettere in relazione tutto ciò che è stato con ciò che è adesso, perché in fondo non ci può essere futuro né innovazione se non si ha memoria del punto di partenza, del percorso creativo che si è conservato e susseguito nei secoli fino a giungere ai tempi attuali.

L’artista sembra voler sfidare l’osservatore invitandolo a giocare con se stesso per riconoscere quelle opere magistrali che spiccano in ambienti improbabili, infatti non si trovano nei musei bensì all’interno di dimore aristocratiche invase da struzzi disorientati, da personaggi dei fumetti o resi fumetti grazie al tratto pittorico di Accardi, eppure in grado di emergere anche in quelle stanze confuse e caotiche. Le citazioni sono molteplici e passano dai busti dell’arte Classica alla Venere del Botticelli, dal Ritratto di Federico da Montefeltro di Piero della Francesca a Modigliani, da Klimt a Escher e poi ancora René Magritte, Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Basquiat, Takashi Murakami, solo per citarne alcuni; ma ciò che diverte di più è trovare una quotidianità surreale, costituita dai personaggi che si aggirano per quelle dimore e che si comportano come se si trovassero a casa loro, rendendo paradossale la coesistenza all’interno delle stanze. Gli struzzi si comportano con disinvoltura, come se per loro fosse normale trovarsi al di fuori del loro ambiente naturale, sembrano essere persino a loro agio nel visitare e scoprire cosa sveli ogni angolo, ogni parete, guardando spesso verso il fruitore come se lo invitassero a partecipare a quel party insolito quanto spassoso.

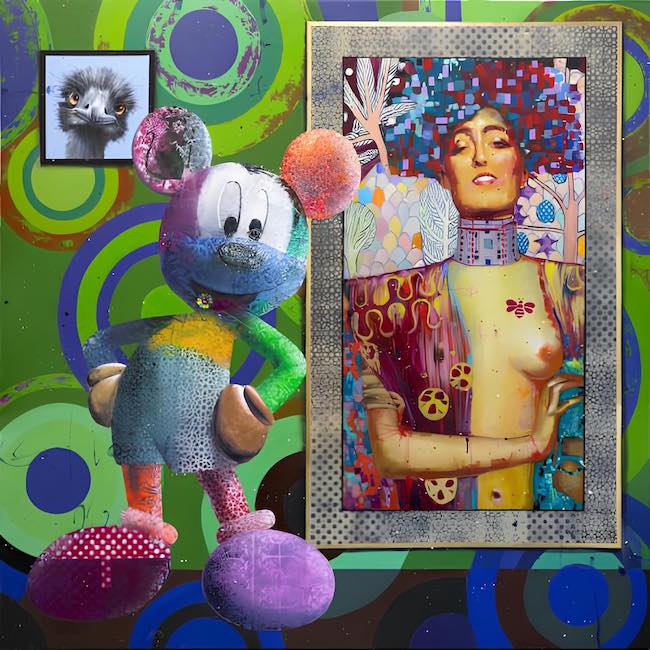

Nell’opera Who painted Mickey Mouse, Angelo Accardi immortala uno dei simboli della Pop Art tradizionale e lo trasforma in un giallo da svelare, indicato dalla domanda nel titolo, incuriosendo il fruitore a focalizzarsi sul topo più famoso del mondo anziché sull’opera alla parete, Giuditta I di Gustav Klimt, che domina di fatto la scena; rivisitata con un mosaico pittorico e attualizzata da un tatuaggio sul petto la donna protagonista sembra invitare l’osservatore a prendersi meno sul serio, pronta a condividere il palcoscenico con Mickey Mouse perché in fondo tutto può cambiare nel corso del tempo e dunque è importante saper mantenere la propria essenza pur adeguandosi a quel cambiamento.

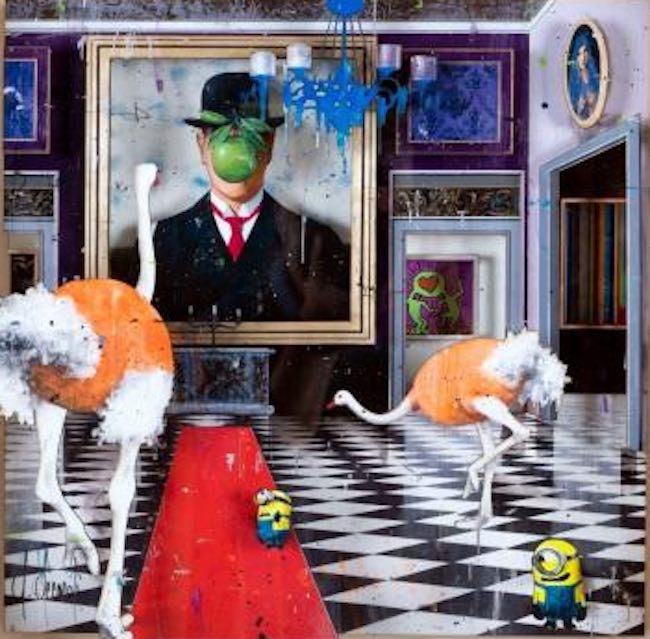

In Magritte on the wall emerge ancor più la vena giocosamente irriverente di Angelo Accardi che in un ambiente sontuoso e suggestivo colloca due struzzi, uno concentrato a trovare la direzione da seguire mentre l’altro assorto nella contemplazione del dipinto Il figlio dell’uomo di René Magritte; in basso, vicini al margine della tela, due Minions che sembrano disorientati ma al tempo stesso sorpresi sia dalla presenza degli uccelli che dal loro inaspettato interesse verso ciò che si trova sulle pareti della stanza. Emerge una sottile considerazione dell’artista sul fatto che chiunque può interessarsi alla bellezza dell’arte se viene messo nelle condizioni di poterla ammirare, di poter lasciarsi conquistare dalla sua armonia; e soprattutto ciò che non dovrebbe mai verificarsi è una catalogazione o l’esaltazione della predominanza di uno stile sull’altro, perché ogni espressione artistica, ogni autore, dovrebbero essere considerati e apprezzati nella loro unicità che può interagire con qualcosa di completamente diverso.

Questa sfumatura emerge dall’opera di Keith Haring situata a fianco di quella di Magritte. E ancora in The Duke in the city, Angelo Accardi riprende il celeberrimo Ritratto del Duca di Montefeltro di Piero della Francesca inserendolo in un contesto Pop dove lo sfondo è costituito dai Circoli di Wassily Kandinsky associato alle Strips paintings di Gerard Richter, dunque un’ambientazione moderna che però si dissocia in qualche modo dal titolo stesso, poiché la città evocata non emerge in alcun modo, inducendo l’osservatore a meditare sul motivo di quel suggerimento non riscontrabile. Ciò che invece è evidente è il richiamo alla natura effettuato da Angelo Accardi, costituita dal panda seduto sul lato sinistro della tela, e il sempre presente struzzo.

Dunque un colpo d’occhio sull’arte di ogni tempo quello di Accardi, per tenere viva e dare una nuova veste a ciò che altrimenti resterebbe ancorato al passato e considerato desueto mentre invece l’arte è eterna ed eternamente si rinnova, è questo il messaggio dell’eccentrico artista. Angelo Accardi è un artista di fama internazionale, ha al suo attivo esclusive mostre personali a Londra e a Mykonos, ed è rappresentato dalle più importanti gallerie d’arte mondiali.

ANGELO ACCARDI-CONTATTI

Email: info@angeloaccardi.com

Sito web: https://www.angeloaccardi.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/angeloaccardiofficial

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/angeloaccardiofficial/

Artworks from the past and out-of-context settings in Angelo Accardi’s Pop Surrealism

Very often, contemporary art tends to forget the origins from which it comes, that past that has inevitably marked the path that followed, and that in fact takes the form today of a freer attitude in the choice of expressive style that each creative wishes to use. There are, however, some artists who, while displaying an unconventional approach to the canvas, feel the need to recount that past, as if their works should become a way of inducing the viewer not to lose memory of how important the masters were who wrote, with their talent, the history of art, more or less recent. Today’s protagonist, through an ironic and irreverent style, constitutes a solo voice on the international art scene, skilfully mixing two of the main styles of the last century and enriching them with a nostalgic touch that is, however, made amusing and unconventional by his ability to play with time and space.

The theme of decontextualisation began to emerge around the 1920s, when a group of French artists outlined the theoretical foundations of a movement, Surrealism, considered the evolution of Dadaism, that wanted to focus its attention on the world of the psyche and the unconscious; André Breton‘s ideas gave rise to a series of personal interpretations, based on the pictorial approach of each adherent to the artistic current, all however with a common denominator, that of deceiving the observer’s gaze with an aesthetic appearance close to reality but in fact leading him into a dreamlike world of nightmares, restlessness, improbable yet potentially possible contexts within the dream dimension. Where disquiet prevailed and took the form of post-apocalyptic scenarios in the artworks of Salvador Dali and Max Ernst, in the Belgian Surrealists such as René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, the sensation aroused was one of reflection, of investigation into those subtle energies brought to light by the artist and communicated to the viewer who could only lose himself in those dimensions, remaining fascinated by the profound meaning hidden within the image.

Decontextualisation, although it emerged in a different manner and with divergent and distant aims from that of Surrealism, was taken up by what is considered the genius creator and founder of Pop Art, that Andy Warhol who was able to perceive the importance of addressing a wider audience, the new emerging middle class who, although not having had a cultural education linked to art, could nevertheless appreciate and wish to bring its beauty into their homes. Thus making the new myths, the symbols of an everyday life and a race for consumerism that was characterising America in the 1950s, the protagonists led Pop Art, declined and adapted to the creative intentions of the various artists who adhered to it, towards planetary popularity. In any case, those symbols, those new myths, comic book characters, Hollywood actors, flags, were not only taken out of their original context, but also highlighted by means of backgrounds in strong colours, their chromatic appearance was modified and adapted to the creativity of the author of the work. The Italian artist Angelo Accardi, originally from a small town in the south of Italy but educated at the Academy of Art in Naples, has over time developed a decidedly original and eccentric painting style, the result of a fusion of different artistic currents of the 20th century that are, however, updated and adapted to his creative impulse; thus, the decontextualisation of Surrealism, which manifests itself in the presence of his ever-present ostriches in domestic settings or on city streets and with a decidedly human appearance in terms of snout expressions, is combined with symbols from comic strips or modern films such as the Minions, the Simpsons, Mister Bean, and the ever-present Mickey Mouse, thus making his artistic production irrevocably Pop.

But Angelo Accardi does not stop there, because in addition to describing the environments in which he places his characters with a realistic touch transformed, however, by an expressionist chromatic range, what makes his canvases even more unique are those continuous references to artworks from the past, that linking everything that has been with what is now, because in the end there can be no future or innovation if there is no memory of the starting point, of the creative path that has been preserved and followed over the centuries until reaching the present day. The artist seems to want to challenge the observer, inviting him to play with himself in order to recognise those masterpieces that stand out in improbable environments, in fact they are not found in museums but inside aristocratic residences invaded by disoriented ostriches, by characters from comic strips or made comic thanks to Accardi‘s pictorial stroke, yet able to emerge even in those confused and chaotic rooms. The citations are many and go from the busts of Classical art to Botticelli’s Venus, from Piero della Francesca’s Portrait of Federico da Montefeltro to Modigliani, from Klimt to Escher, and then on to René Magritte, Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Basquiat, Takashi Murakami, to name but a few; but what is most amusing is to find a surreal everyday life, made up of the characters who wander around those dwellings and behave as if they were at home, making the coexistence within the rooms paradoxical. The ostriches behave casually, as if it were normal for them to be outside their natural environment; they even seem to be at ease visiting and discovering what each corner, each wall, reveals, often looking towards the viewer as if inviting him to join in that unusual yet hilarious party. In the artwork Who painted Mickey Mouse, Angelo Accardi immortalises one of the symbols of traditional Pop Art and transforms it into a detective story to be unveiled, indicated by the question in the title, intriguing the viewer to focus on the world’s most famous mouse rather than on the work on the wall, Gustav Klimt’s Judith I, which actually dominates the scene; revisited with a pictorial mosaic and brought up to date by a tattoo on her chest, the woman protagonist seems to invite the observer to take herself less seriously, ready to share the stage with Mickey Mouse because, after all, everything can change in the course of time and therefore it is important to be able to maintain one’s essence while adapting to that change. In Magritte on the wall, Angelo Accardi‘s playfully irreverent vein emerges even more. In a sumptuous and evocative setting, he places two ostriches, one concentrated on finding the direction to follow while the other is absorbed in contemplation of René Magritte’s painting The Son of Man; below, close to the edge of the canvas, two Minions who seem bewildered but at the same time surprised both by the presence of the birds and by their unexpected interest in what is on the walls of the room. What emerges is a subtle consideration of the artist that anyone can be interested in the beauty of art if they are put in a position to be able to admire it, to be conquered by its harmony; and above all, what should never occur is a cataloguing or exaltation of the predominance of one style over another, because every artistic expression, every author, should be considered and appreciated in their uniqueness that can interact with something completely different.

This nuance emerges from Keith Haring’s artwork situated next to that of Magritte. And again in The Duke in the city, Angelo Accardi takes Piero della Francesca’s famous Portrait of the Duke of Montefeltro, inserting it in a Pop context where the background is constituted by Wassily Kandinsky’s Circles associated with Gerard Richter’s Strips paintings, thus a modern setting that is somehow dissociated from the title itself, since the city evoked does not emerge in any way, inducing the observer to meditate on the reason for that suggestion that cannot be found. What is instead evident is the reference to nature made by Angelo Accardi, consisting of the panda sitting on the left side of the canvas, and the ever-present ostrich. So, that of Accardi is a glimpse into the art of all times, to keep alive and give new life to what would otherwise remain anchored in the past and considered obsolete, whereas art is eternal and eternally renews itself, this is the message of the eccentric artist. Angelo Accardi is an internationally renowned artist, has exclusive solo exhibitions in London and Mykonos to his credit, and is represented by the world’s most important art galleries.